Bone Density Loss

Bone Density Loss

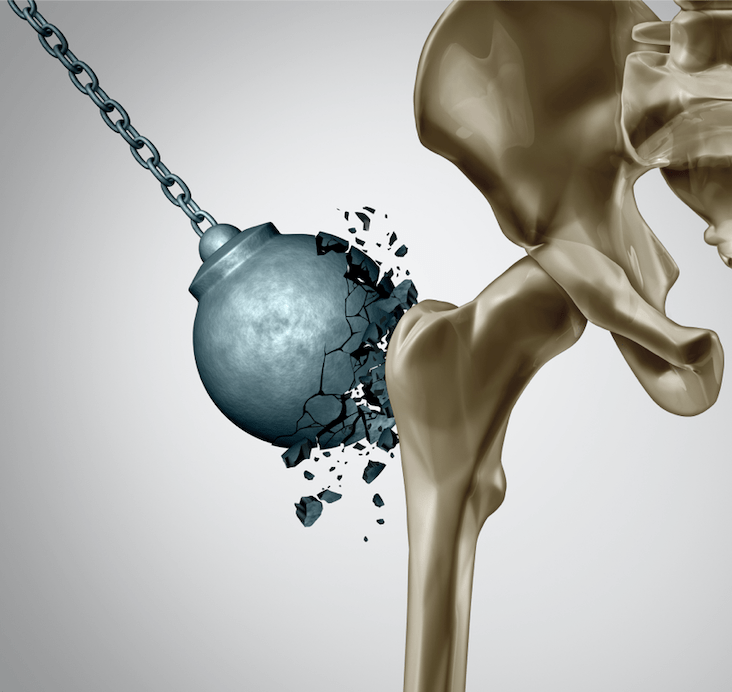

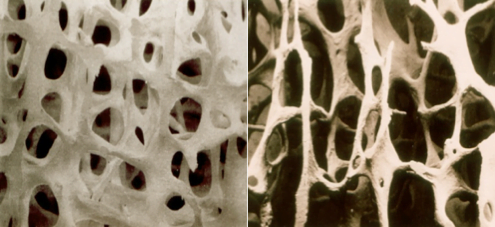

One in two women and one in three men over the age of 50 suffer from bone loss. This is a condition in which the hard, outer-shell of bones thins, and the holes in cancellous bone get larger. Mild loss is referred to as osteopenia, while significant loss is defined as osteoporosis.

Numerous factors affect bone health, which we cannot control such as our age, gender, menopausal status, and having a family history of weak bones. On the the other hand there are a lot of factors we can control. In practical terms, the factors which affect bone health can be split into three categories.

Medical factors which increase bone loss:

- Any chronic illnesses that cause disability and make a person less mobile

- Spontaneous early menopause in women

- Surgery or radiotherapy to the ovaries or testes (usually part of medical treatment)

- Diabetes, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic liver or kidney disease

- Inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

- Overactive thyroid disease

- Eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa

Drugs, taken over a long time, which increase the risk of bone density loss:

- Aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer (e.g. anastrozole, letrozole and exemestane)

- LHRH agonists such as Goserelin (e.g. Zoladex®)

- Chemotherapy which damages ovarian function (in premenopausal women)

- Some chemotherapy agents specifically damage bones (e.g. methotrexate)

- Newer Immunotherapy cancer treatments ( e.g. imatinib, nilotinib and dasatinib)

- Some anti-epileptic drugs (e.g. phenytoin)

- Warfarin

- Proton pump inhibitors for indigestion (e.g. omeprazole, lanzoprazole)

Lifestyle factors which increase the risk of bone density loss

- Lack of physical activity

- Low body weight (BMI<20kg/m2)

- Drinking more than 3.5 units of alcohol / day

- Smoking

- Lack of sun exposure

- Poor diet

Medical treatments designed to help improve bone density

Correct underlying contributory medical conditions: Underlying medical conditions should be investigated and treated. Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) has been proven to be particularly effective at improving the bone health of postmenopausal women, although it should be remembered that prolonged use can increase breast cancer risk. Among men, low testosterone levels caused by cancer treatments can lead to a decline in bone density, making testosterone replacement treatment a viable option for those looking to improve bone health. Testosterone replacement is usually regarded as unsuitable for men with prostate cancer as it can encourage prostate cancer cells to grow, yet evidence has emerged which suggests that correcting low testosterone levels in men with low-risk prostate cancer improves their bone density as well as their quality of life.

Calcium and vitamin D supplements: There is conflicting evidence surrounding the supposed benefits of calcium supplements taken to support bone health. Some studies suggest some effectiveness if taken alongside additional medical or lifestyle interventions [Ryan, Swenson], while others have indicated no benefit [Datta, Record]. A recent meta-analysis of 59 RCTs found very little clinical benefit in terms of bone density measurement or risk of fractures [Tai]. Of more concern, another meta-analysis of 15 RCTs, also published in the BMJ, reported that these supplements are associated with an increase in cardiovascular disease and heart attacks [Bollard]. Conversely, another study, specifically involving women taking aromatase inhibitors, found that high dose vitamin D with calcium helped reduce joint pains [Prieto-Alhambra], although this was likely due to the intake of vitamin D rather than calcium. In general, the evidence suggests that these supplements should only be taken to correct specific calcium or vitamin D deficiencies or to support bisphosphonates therapies.

Bisphosphonates: These are drugs that interfere with osteoclast function, increasing bone density and reducing the risk of fractures. They have been shown to help age-related osteoporosis and prevent bone loss caused by hormonal therapy and other cancer treatments. There are several bisphosphonates used to treat osteoporosis, including alendronic acid, ibandronic acid, risedronate sodium, and zoledronic acid. A rare side effect of bisphosphonate treatment is osteonecrosis of the jaw. It happens when healthy bone tissue in the jaw becomes damaged and dies. This can cause loosening of the teeth and problems with the way the gums heal. This very infrequently happens with oral bisphosphonate and very rarely with the doses given for osteoporosis. If you haven’t been to the dentist for six months before starting these drugs, it’s essential that you go for a check-up before taking them.

Denosumab is a targeted antibody treatment that again impairs osteoclastic activity. It is often used if bisphosphonate drugs are not tolerated, although some doctors choose them from the very start because they only require a subcutaneous (under the skin) injection once every six months. If you are taking denosumab, your doctor may advise you to take calcium and vitamin D supplements.

Raloxifene is used to prevent and treat osteoporosis in women who have experienced menopause. The drug shares some of the helpful effects of oestrogen, reducing the breakdown of bone and the risk of fractures. It’s used only for women who can’t take bisphosphonates. Women with breast cancer who are treated with tamoxifen should not take raloxifene. This is because it may interfere with tamoxifen.

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is a naturally occurring hormone that’s produced by the parathyroid glands, which are attached to the thyroid gland in the front of the neck. PTH stimulates bone formation and helps the body absorb calcium. There’s a synthetic version of PTH which can be injected just under the skin every day for a maximum of 24 months. It’s more likely to be given to people who have broken bones caused by severe osteoporosis but is not given to people with bony metastasis.

Lifestyle Strategies to help bone health

.

1. Exercise:

General advice on exercise aimed at improving bone health: It’s best to find something you enjoy, especially if it also has a sociable element, so you’ll carry on with it and not get bored. Exercise needs to be done regularly to have the maximum benefit. When exercising, try to push yourself and add some weights and resistance, but do not push yourself too hard at first. At the end of an activity, you should feel warm and slightly out of breath, but not exhausted. With practice, you’ll soon find you’re able to do more. Weight-bearing and resistance exercises are ideal as these send signals to the cells in the bone to lay down more calcium and harden them, but it is important you also exercise your whole body and perform different types of exercise.

High-intensity resistance and impact training (HiRIT) has been shown in a recent randomised trial from Australia to improve bone density (and physical strength) in both the hips and back with no increased risk of fractures. The HiRIT program consisted of resistance exercises including the deadlift, overhead press, and back squat, performed in five sets of five repetitions. The impact loading exercise was a jumping chin-up with a drop landing. Obviously, this is something to work up to, preferably with supervision.

Aerobic exercises that raise the heart rate for 30 minutes five times a week are particularly beneficial. This type of aerobic activity strengthens and protects the heart, lungs and metabolism, while helping maintain a healthy body weight. Weight-bearing aerobic exercises such as walking, jogging, skipping, climbing stairs, dancing and hiking, are ideal for increasing bone density. Exercises such as swimming and cycling are good for your heart and lungs but are not weight-bearing.

Resistance exercises involve making your muscles work harder than usual, against some form of resistance. They strengthen muscles, bones and joints. They may also improve your balance. The exercises can be done with hand weights, machines or elastic bands.

Anaerobic exercises: These are exercises which use up more oxygen than you can replace by making you breathe faster, creating an oxygen debt. When you stop anaerobic exercises you have to breathe heavily until you have paid back this debt. Examples would be fast running, cycling, rowing or swimming. It is good to introduce an element of this in every session, but only after reaching a suitable level of fitness and ensuring you warm-up and stretch beforehand.

Safety issues whilst exercising: Exercise is very safe, especially if you join a supervised exercise programme. If you get chest pain or extreme shortness of breath after starting you need to consult your GP. Remember to always warm-up and warm down with aerobic exercises and stretching. If you have severe osteoporosis already, it may be better to avoid high impact exercises such as jogging, skipping, racquet sports like tennis, and some types of dancing, until your bones start healing. Instead, start with low impact exercises such as walking (either outside or on a treadmill machine), climbing stairs, or using a cross-trainer.

2.Nutrition and bone health

2.Nutrition and bone health

Dietary calcium: A daily intake of 700mg of calcium is recommended for adults. If you have osteoporosis, your doctor may advise you to take more (1,000 to 1,200mg a day). To get enough calcium daily it is advisable to eat foods that are rich in calcium, such as:

- Dairy products (contain the highest amounts of calcium)

- Tinned oily fish (sardines are particularly good)

- Leafy green vegetables (e.g. broccoli, curly kale)

- Nuts

- Soya beans, tofu, kidney beans, baked beans

- Dried fruit (e.g. figs, apricots, raisins)

If you have a dairy-free diet, make sure you eat non-dairy foods that contain calcium. You may also choose to take products with added calcium. These include some types of fortified non-dairy milk. Always shake the carton well before use to ensure calcium is mixed throughout the drink. Some foods and drinks upset the calcium balance in the body. These include caffeine, red meat, salt, and fizzy drinks that contain phosphates, such as Cola. Avoid having large amounts of these.

Strategies to enhance Vitamin D levels (more)

- Cover their skin when outside

- Have dark skin (e.g. African, African-Caribbean, South Asian backgrounds)

- Do not spend regular time out of doors (e.g. housebound or in care homes)

The most effective way to increase Vitamin D levels is to ensure regular but gentle exposure to the sun. Vitamin D has a half-life of 6 weeks, so by mid-winter, most of us will have some degree of vitamin D deficiency. Only 10-15 minutes of sun exposure is necessary to start the production of vitamin D, but precautions need to be taken to avoid burning while sunbathing, as this will create thin, sun-damaged skin, lead to premature ageing, and increase the risk of skin cancers. Try to expose areas of the skin that get the least sun exposure such as the stomach, while protecting areas such as the face, hands and upper chest. Remember to use total barrier sunblock on areas which have received radiotherapy. For those who have undergone chemotherapy, take particular care as chemotherapy agents can sensitise the skin and increase the likelihood of burning.

Modulating the carcinogenic effects of the sun: As well as the measures outlined above, try to reduce exposure to other carcinogens which enhance the harmful effects of the sun, particularly smoking. Stay away from carcinogenic foods and try to eat extra polyphenol-rich foods which ensure the body’s antioxidant enzymes are in good working order. A good quality after-sun, preferably with olive oil added due to the oil’s known effectiveness at enhancing DNA repair, is also highly recommended.

Tanning beds: The benefits of tanning beds are unlikely to counterbalance the risks. Some authors advise use over the winter months in order to maintain vitamin D levels. However, in a recent study, The Lancet Oncology commented that sunbeds pose as big a cancer risk as tobacco and asbestos. It reported a new analysis of some twenty studies, which concluded that the risk of skin cancer jumps by 75% when people start using tanning beds before the age of 30.

- Oily fish such as mackerel, sardines and anchovies

- Sun dried mushrooms

- Grass-fed meat and liver

- Free-range chicken or game egg yolks

Manufactures are creating pills with ever increasing doses on vitamin D but research is showing us that it’s not the amount in the gut but how much is absorbed which matters. If you have the the wrong type of bacteria, or an inflamed gut wall, your absorption of vitamin will be very low. Low vitamin D levels, along side a leaky gut, both leading to chronic inflammation, is a perfect storm for ill health.

Several clinical trials have reported that oral Lactobacillus probiotic strains resulted in significantly increased serum vitamin D3 levels. Researchers have shown that the likely mechanism for this is increased lactic acid production from the probiotic bacteria, which in turn increases the enzyme responsible for vitamin D absorption and synthesis.

Yourgutplus+ has an ideal concentration of lactobacillus, vitamin D and inulin. It was selected for the UK National Nutritional Covid intervention study, the first paper was published in Nov 2021 and found a link between this lactobacillus blend with enhanced recovery from early and long covid [Read full paper].

The recommended daily amount (RDA) of vitamin D for adults is around (600-800 iu /day), but more is necessary if there is a history of deficiency or bowel malabsorption. Government websites advise taking over the counter Vitamin D supplements, and people who have a higher risk of vitamin D deficiency are advised to take a vitamin D supplement all year round and at a higher dose of 1000 ui. Vitamin D toxicity is extremely unlikely through diet and sun exposure alone, with toxicity caused by repeated megadoses of vitamin D supplements (over 50,000 iu a day for several months). Unless you have a known vitamin E deficiency, ensure the supplement you buy over the counter does not contain added vitamin E, something which is commonplace among many brands.

3. Other dietary and lifestyle influences on bone density

In terms of which polyphenols have the greatest benefit, the isoflavones and flavanoids are particularly beneficial [Droke, McTiernan, Hardcastle, Fujii, Merill, McTiernan, Marini]. Green tea, as well as having antioxidant properties, reduces inflammation and has been shown to inhibit inappropriate osteoclatogenesisi [Shen Chwan-Li et al]. Curcumin appears to be particularly potent in protecting BMD in ovariectomised animals with doses which could be easily achieved in humans, albeit with some supplementation [Ki, Wright].

There is substantial evidence to suggest that polyphenol-rich foods or supplements would be a good dietary option when considering bone health [Sacco, Hubert]. In this website, we have highlighted recipes which increase polyphenol and plant protein intake, but, unless concerted daily efforts are made, a polyphenol-rich supplement such as Pomi-T may be necessary when looking to maintain appropriate levels.

Vitamin K2 (Menaquinone ): Phylloquinone (vitamin K1) is essential for the formation of several clotting factors and is the target for warfarin. It is exclusively synthesized in green plants, and severe deficiency will cause bleeding disorders. More recently, its relevance to bone health has emerged, with a variant formed by the bacterial fermentation of foods (see below) called menaquinones (vitamin K2) identified as particularly important. Although more research is needed, it appears that vitamin K2 helps harden the bones as it is required for the Gamma carboxylation of osteocalcin, a bone matrix protein which is made in osteoblasts to form bone. Numerous studies have reported that elderly people with hip fractures have a lower level of Vitamin K2 than the general population [Hodges], while an animal study demonstrated that a diet rich in vitamin K2 prevented ovariectomy-induced bone loss [Yamaguchi].

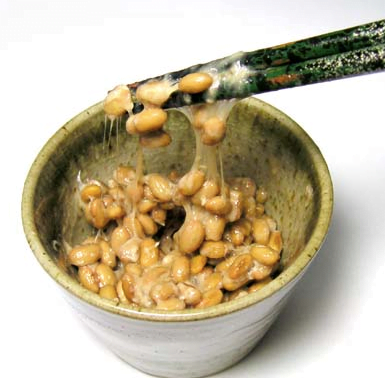

How to increase dietary vitamin K2 levels: The most notable source of vitamin K2 is a fermented soya dish called natto, popular in Japan. It is very high in vitamin K2, containing >1000 μg /100g), with the next nearest foods being cheese (60 μg/100g) or curd at 24 μg/100g. Studies from Japan have shown that consumption of natto up to three times a week significantly increased serum vitamin K2 levels as well as gamma carboxylated osteocalcin, a marker of fracture risk [Tsukamoto]. There is one main drawback to natto – it is something of an acquired taste. Alternative dietary sources are listed below, but dietary supplements can ensure adequate intake. In summary, dietary sources of vitamin k2 include:

- Natto

- Cheese and Curd

- Sauerkraut and Kimchi

- Seaweed

- Other fermented products (e.g. Miso soup, Serrano ham, tempura)

4. Trace minerals

It is not just calcium and proteins which make up healthy bones, other minerals have a role too, albeit to a lesser extent [Eaton-Evans]. Experimental and epidemiological studies suggest low magnesium has harmful effects on bones [Catiglioni]. Magnesium deficiency contributes to osteoporosis directly by acting on crystal formation and on bone cells, and indirectly by impacting on both the secretion and activity of the parathyroid hormone and by promoting low-grade inflammation. Other trace minerals such as zinc, manganese and copper may be important in maintaining bone quality via their role as metalloenzymes in the synthesis of collagen and other proteins that form the structure of bone [Gür]. Animal experiments inducing deficiencies in these trace minerals cause bone loss [Saltman].

Unfortunately, suboptimal levels of minerals are becoming alarmingly commonplace. As countries get richer, the diversity of the typical diet actually shrinks. Today, 75% of the world’s food supply comes from only 12 plants and five animal species. What’s more, in the race to get large quantities of affordable food, modern intensive farming, overcleaning and processing are depleting minerals from many foods on the shelves.

Some nutritional tips are summarised below but a good why of ensuring adequate essential mineral intake is with a good quality mineral supplement such as PhytoMineral.

Magnesium

- Fish such as Halibut and other white fish

- Almonds and cashews

- Soybeans

- Other nuts

- Whole potatoes

Zinc (more about dietary zinc)

- Oysters, crab, lobster, clams and shrimp,

- Seaweed

- Cashew nuts

- Sesame seeds

- Parsley and spinach

- Quinoa and lentils

- Crimini and shiitake mushrooms

- Dark chocolate

Copper

- Whole grains and beans

- Nuts and sunflower seeds

- Whole potatoes and leafy dark green vegetables

- Dark Chocolate

- Black pepper

- Organ meats (kidneys, liver)

- Yeast

5. Other negative lifestyle factors

5. Other negative lifestyle factors

Sleep disturbance: Lack of sleep affects many biological systems and more recently there is growing evidence suggests sleep is also important for optimal bone health. Sleep is regulated by a complex interaction between our endogenous circadian rhythm. Sleep and circadian disturbances also indirectly affect bone health through an increased risk of falls and fractures. The answer is not to take traditional medications (sleeping tablets) commonly used for insomnia as they are associated with an increased risk of falls and fractures. Instead, it would be a good idea to adopt sleep hygiene rules and consider a natural, non-sedatory sleeping aide such as Phyto-nightplus+

Smoking: The list of health risks associated with smoking only gets longer and longer. Loss of bone density is just one of them. If you smoke, see tips to quit.

Alcohol: Greater bone density was found in men consuming seven or more alcoholic beverages weekly than in non-drinkers, highlighting the potential benefits of low to moderate alcohol consumption. On the other hand, men with high alcohol intake had a worse BMD.

Weight optimisation: A 2007, US-based study, reported that heavier people had better bone density. The same authors, in another study, also reported that among breast cancer survivors, smoking and being underweight (BMI less than 19) were associated with lower BMD. If you are underweight (Body Mass Index <20 kg/m2), it would be worth bulking up with a combination of carbohydrates, proteins and weight-bearing exercises.

References to bone health advice pages

Rendina E et al. Dried plum’s capacity to reverse bone loss and alter bone metabolism in post menopausal osteoporosis model. Plos one, 2013.Doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0060569

Droke E et al. Soy isoflavones avert chronic inflammation-induced bone loss and vascular disease. J Inflammation 2007; 4(17).

Garrett R et al. Oxygen-derived free radicals stimulate osteoclastic bone resorption in rodent bone in vitro and in vivo.J Clin Invest. 1990; 85(3):632-9.

Hardcastle AC et al. Associations between dietary flavonoid intakes and bone health in a Scottish population.J Bone Miner Res. 201; 26(5):941-7.

Sacco SM et al. Phytonutrients for bone health during ageing. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013; 75(3):697-707.

Hubert P et al Dietary Polyphenols, Berries, and Age-Related Bone Loss: A Review Based on Human, Animal, and Cell Studies Antioxidants (Basel), 2014 ; 3(1): 144–158.

Trzeciakiewicz A et al When nutrition interacts with osteoblast function: molecular mechanisms of polyphenols. Nutr Res Rev. 2009; 22(1):68-81.

Shen Chwan-Li et al Green Tea and Bone metabolism. Nutr Res. 2009; 29(7): 437-56

Wright LE, et al. Protection of trabecular bone in ovariectomized rats by turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) is dependent on extract composition.. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010;58(17):9498–504.

Kim W et al. Curcumin protects against ovariectomy-induced bone loss and decreases osteoclast activity. J Cell Biochem 112:3159-99.

Nair R et al. vitamin D; the Sunshine vitamin. J Pharmacol pharmacother 2012; 3(2): 118-126

Catiglioni S et al Magnesium and Osteoporosis: Current State of Knowledge and Future Research Directions. Nutrients 2013; 5(8): 3022–3033.

Saltman P et al The role of trace minerals in osteoporosis. J Am Coll Nutr. 1993; 12(4):384-9.

Gür A The role of trace minerals in the pathogenesis of postmenopausal osteoporosis and a new effect of calcitonin. J Bone Miner Metab. 2002; 20(1):39-43

Eaton-Evans J et al. Osteoporosis and the role of diet Br Journal Biomed Sci 1994;51(4):358-70.

Kurnatowska I et al. Effect of vitamin K2 on progression of atherosclerosis and vascular calcification in nondialyzed patients with chronic kidney disease. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2015;125(9):631-40.

Shea MK, and Holden RM. Vitamin K status and vascular calcification: Evidence from observational and clinical studies. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(2):158-165. doi: 10.3945/an.111.001644.

Chiang S et al. Antiosteoporotic effects of Lactobacillus -fermented soy skim milk on bone mineral density and the microstructure of femoral bone in ovariectomized mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2011, 27; 59(14):7734-42.

Yacon F et al. Bifidobacterium longum modulate bone health in rats. J Med Food. 2012; 15(7):664-70.

Ohlsson C et al Probiotics protect mice from ovariectomy-induced cortical bone loss. PLoS One. 2014; 17; 9(3):e92368.

Reid G et al. New scientific paradigms for probiotics and prebiotics. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003; 37(2):105-18.

Tsukamoto Y et al Intake of fermented soybean (natto) increases circulating Vitamin K2 and gamma-caboxylated osteocalcin concentrations in normal individuals. J Bone Miner Metab (2000) 18:216-222.

Caraballo PJ, Heit JA, Atkinson EJ, Silverstein MD, O’Fallon WM, Castro MR, Melton LJ III (1999) Long-term use of oral anticoagulants and the risk of fracture. Arch Intern Med 159: 1750–1756.

Hodges SJ, et al. Circulating levels of vitamins K1 and K2 decreased in elderly women with hip fracture. J Bone Miner Res 1993; 8:1241– 1245.

Jie K-SG, Bots ML, Vermeer C, Witteman JCM, Grobbee DE (1995) Vitamin K intake and osteocalcin levels in women with and without aortic atherosclerosis: a population-based study. Athero- sclerosis 116:117–123.

Shanahan CM, et al (1999) Medial localization of mineralization- regulating proteins in association with Mönckeberg’s sclerosis. Circulation 100:2168–2176.

Yamaguchi M Effect of vitamin K2 in fermented soybean (natto) on bone loss in ovariectomised rats. J Bone Miner Metab 17:23-29.

Beulens JW, Bots ML et al. High dietary menaquinone intake is associated with reduced coronary calcification. Atherosclerosis. 2009 Apr;203(2):489–493.

Geleijnse JM, Vermeer C et al. Dietary intake of menaquinone is associated with a reduced risk of coronary heart disease: The Rotterdam Study. J Nutr. 2004;134(11):3100-3105.

Harshman SG, and Shea MK. The role of vitamin K in chronic aging diseases: Inflammation, cardiovascular disease, and osteoarthritis. Curr Nutr Rep. 2016;5(2):90-98.

Tai V et al calcium and vitamin D supplements and bone health – a metanalyisis of randomized trials BMJ 2015; 351:h4183.

Bollard et al Calcium supplements and the coronary arterial disease – a meta-analysis of randomized trials BMJ 2010; 341:c3691.

Prieto-Alhambra D et al. Vitamin D threshold to prevent aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia: a prospective cohort study. Breast cancer Res Treat 2011;125(3):869-78

Datta M et al Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation and Loss of Bone Mineral Density in Women Undergoing Breast Cancer Therapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2013; 88(3)

Lazzeroni M, Serrano D, Pilz S, et al. Vitamin D supplementation and cancer: review of randomized controlled trials. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2013;13(1):118-125.

Schwartz G.G. Vitamin D, sunlight and the epidemiology of prostate cancer. Anti-Cancer Agent Me 2013;13(1):45-57.

Chiang KC and Chen TC. The Anti-cancer Actions of Vitamin D. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2013;13(1):126-39.

Zgaga L et al. Plasma Vitamin D Concentration Influences Survival Outcome After a Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer. JCO 2014;32(23):2430-2439.

Ng K et al. Circulating 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels and Survival in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. JCO 2008;26(18):2984-2991.

Rose AA et al. Blood levels of vitamin D and early stage breast cancer prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJC 2001;85(10):1504–1509.

Mondul AM, et al. Circulating 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Prostate Cancer Survival. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2016; 25(4):665-9.

Pilz S et al. Vitamin D and cancer mortality: systematic review of prospective epidemiological studies. Anti-Cancer Agent Me 2013;13(1):107-117.

Giovannucci E. Epidemiology of vitamin d and colorectal cancer. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2013;13(1):11-19.

Luscome C et al. Prostate cancer risk: associations with ultraviolet radiation, tyrosinase and melanocortin-1 receptor genotypes. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013;141(3):331-339.

van der Rhee H, Coebergh JW and de Vries D. Is prevention of cancer by sun exposure more than just the effect of vitamin D? A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Eur J Cancer 2013;49(6):1422-1436.

Brown JK, Byers T, Doyle C, et al. Diet and physical activity during and after cancer treatment: An American cancer society guide for informed choices. CA Cancer J Clin 2003; 53(5): 268-291.

Twiss et al., 2001, Mackay & Joy 2005, Tanna N. Nurs Times 2009;105:28)

Waltman NL et al.; The effect of weight training on bone mineral density and bone turnover in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors with bone loss: A 24-month randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int 2010; 21(8): 1361-1369.

McTiernan A, and Wactawski-Wende J. (2009). Low-fat, increased fruit, vegetable, and grain dietary pattern, fractures, and bone mineral density: the Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial. Am J Clin Nutr 89(6): 1864-76.

McNeeley M, Campbell K, Rowe B et al (2006) Effects of exercise on breast cancer patients and survivours: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Canadian Medical Association Journal 175:34-41.

Saad F, Adachi JD, Brown JP et al. Cancer Treatment – Induced Bone Loss in Breast Cancer and Prostate Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5465-76.

The RECORD Trial Group. Oral vitamin D3 and calcium for secondary prevention of low-trauma fractures in elderly people (Randomised Evaluation of Calcium Or vitamin D, RECORD): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet 2005, 365 (9471; 1621-28

Andersen BN, Johansen PB, Abrahamsen B. Proton pump inhibitors and osteoporosis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 28(4):420–425, 2016.

Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: A pharmacoepidemiological claims database analysis. JAMA Neurol. 73(4): 410–416, 2016.

Ito T, Jensen RT. Association of long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy with bone fractures and effects on absorption of calcium, vitamin B12, iron and magnesium. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2010;12(6):448–57,

[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

Bone Density Loss

Bone Density Loss